Ponthendre or Pont-hendre (and even Pont Henry in old documents and local parlance) is a Welsh name. Pont means Bridge, while hendre is a winter farmhouse. Traditionally, Welsh farmers wintered their livestock in the valley and in the summer took them to the upland grazing and stayed at a hafod or summer farmhouse.

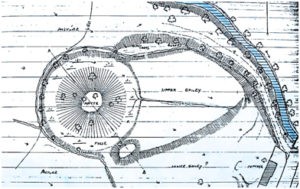

The earthworks above Ponthendre have all the apppearance of a textbook early Norman motte and bailey castle. They are located on a spur of high ground pointing into the valley of the River Monnow, where it is joined by the Olchon Brook. A ditch was quarried across the spur and the rock and soil was piled up to make a high mound or motte, 44 metres across and 10.5 metres high. This was surrounded by a waterfilled moat. A crescent-shaped area to the east of the motte was levelled and surrounded with a low rampart that enhanced the natural scarp slope. The south side also had a wet ditch, while the east side was protected by the steep slope down to the Olchon.

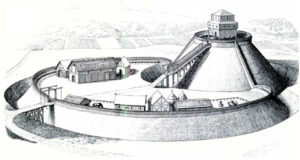

Before the earthworks were built, this was woodland. Clearing the site itself and a bowshot all around would have involved cutting down several hundred trees. These would normally be used to build a tower within a stockade on the top of the motte and a palisade around the bailey.  A bridge would be constructed from the bailey to the motte, and housing for soldiers and their horses.

A bridge would be constructed from the bailey to the motte, and housing for soldiers and their horses.

Our excavations in 2016 annd 2017 showed that, although the earthworks were apparently complete, none of this necessary building work took place. We found no sign of any occupation, no foundations, no hearths or discarded bones from feeding the troops, and almost no broken pottery. There was a small fragment of cooking pot below the rampart, of a type found at other early Marches castles, and a handful of other pieces of mixed dates that probably arrived later with farmyard manure.

Clearing the site and building the earthworks involved an enormous amount of labour. The motte alone contains around 14,000 tonnes of earth and quarried stone. So why did the construction stop and why did nobody come back to finish the job? Perhaps we should begin by asking why they wanted a castle here in the first place?

It has been suggested that Ponthendre was being built as an outlying defence providing advance warning for any attack on Longtown. Being just over half a mile away it wouldn’t give much warning, and why was an outpost necessary when Walter de Lacy already had his first motte and bailey at Walterstone, only 3 miles to the south? If Longtown needed a fortified observation post it would be on its north side and not to the south. We can therefore discount any idea that the de Lacys had a castle at Longtown when they began building Ponthendre.

Ponthendre was clearly intended to defend Clodock from a threat emanating from further north. It is generally recognised that Longtown is an ideal site for a castle. The Romans knew this a thousand years earlier when they built their fort and it seems Harold Godwinson had seen the benefit of placing his army there in 1055. So why did the Normans start building at Ponthendre instead of Longtown?

The most obvious answer is that Longtown was already occupied and well defended. Walter de Lacy had been charged with defending the border, not starting a war with the Welsh, so it would be a sensible policy to build a motte and bailey to control the road south from Longtown. The border between England and Wales would then be defined as where the Olchon Brook crosses the valley.

As Ponthendre was never completed, it is clear that this policy soon went wrong and the Normans were forced to drive the Welsh out of Longtown and secure its rampart for their own use. They built a new motte on the corner of the rampart and crowned it with a wooden tower, perhaps using the timber intended for Ponthendre.

Longtown Castle did eventually get its northern observation post – Mouse Castle at Cusop, probably built by Walter’s son, Roger de Lacy, on the remains of an old Iron Age fort. The Welsh name for this castle was Llygad, meaning the Eye, later confused with Llygod, meaning mice.