The almost square rampart of Longtown Castle has long suggested that the site may have originally been a Roman fort. Previous excavations on the site have, however, failed to uncover any Roman remains. During 2016, a section through the rampart on Castle Green showed that the base of the rampart was composed of piled-up turf, the material used by the Romans for the first construction of a fort.

During 2017, the two trenches at the north end of the eastern bailey both revealed Roman pottery, about 1m down and close to the bedrock. This was radiocarbon dated to the first century AD. More Roman pottery was found in the higher medieval levels – a consequence of heavy disturbance on the site in later centuries.

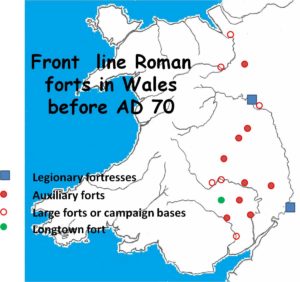

Two of the pottery pieces are often associated with military sites – a stepped flagon neck of Severn Valley ware and a large piece of amphora of the Dressel 20 type*. These pottery pieces and the square shape of the rampart provided evidence that we were dealing with an auxiliary fort. Forts of this shape and size, around 1.5 – 2 hectares (3.5 – 5 acres), are relatively common across Wales and the Marches, with at least 20 known sites, and would have been garrisoned by a cohort of 500 foot soldiers. The larger rectangular forts housed both cavalry and foot soldiers.

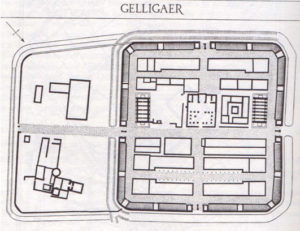

Initially, the forts would have been built with turf ramparts about 2m high with a wooden palisade and ditch, sometimes with another ditch further out. Some, like Gelligaer in the South Wales valleys, had an additional annex attached to one side of the fort. It is entirely possible that Longtown’s northern bailey, thought to have been medieval in origin, may have originated as one of these annexes. Some of the forts were later rebuilt in stone, which gives us an insight into their internal structure; most had a central principia, or headquarters building, granaries, outbuildings for storage and livestock and, of course, multiple barracks for the troops.

Longtown fort was never rebuilt in stone, which suggests that it was built as an early frontier fort, probably constructed between AD47 and AD55. This was the time when the Roman legions campaigned against the Silures and the Ordovices, two tribes occupying the southern and northern parts of modern Wales, who were hostile to Rome. A radiocarbon date from charcoal taken from the turf layers at the base of the rampart was consistent with the fort being built during the early Roman occupation of Britain.

Situated on the Silures eastern border, the Longtown area would have been in the first line of attack by the Romans. As the legions advanced westwards, territory gained was consolidated by the building of forts, initially from Usk in the south to Wroxeter in the north and beyond. These early forts were placed within a day’s march of each other, to ensure that any attacks could be quickly reinforced. Tacitus (1) gives us a very vivid description of the campaign and the problems the Romans had to face:

‘some legionary cohorts, left behind to construct garrison-posts in Silurian territory, were attacked from all quarters and, if relief had not quickly reached the invested troops from the neighbouring forts – they had been informed by messenger – they must have perished to the last man. As it was the prefect [fort commander] fell, with 8 centurions and the boldest members of the rank and file. Nor was it long before a Roman foraging party and the squadrons despatched to its aid were totally routed.’

Until now, a notable gap in the network of known forts between Usk and Leintwardine has existed (2) leaving a 2-day march between Abergavenny (Gobannium) and Clyro on the Wye. This gap is now filled by the fort at Longtown. Once the front line of conflict moved on, these smaller forts would have been manned by auxiliary troops recruited from the provinces for policing and peace-keeping duties. We know from Roman military records that 4 of these cohorts operated in the South Wales area around 100AD, under the command of the Caerleon legion. One of these cohorts, the 1st Alpinorum, seems to have a very apt name for a unit operating in the Black Mountains, but of course we have no way of knowing if this was the unit stationed at Longtown.

With a garrison of 500 soldiers, the Longtown fort would have needed constant resupplying from the towns of Gobannium (Abergavenny) or Magnis (Kenchester) on the Wye, both a day’s march away. The lines of Roman roads to both towns can be traced with some sections still in use today.

By 78AD the war against the Silures and Ordovices was over and the legions turned their attention to the north and Caledonia. Longtown fort would have continued its policing role for some time afterwards, but was probably abandoned sometime in the 2nd century AD. Nevertheless, the Roman roads would have continued to be used for centuries after. Even sections not in use today can be found on maps of the early 1800s.

During the following nine centuries the ramparts decayed and the ditches partly filled in, but we know that the site did not return to woodland. The nature of the soil excavated during the project testifies to that. It seems likely that people continued to live here grazing the land with livestock.

- Tacitus. The Annals. Book 12, 38. Tr. John Jackson, Delphi Classics 2014

- Burnham, B.C. and Davies, J.L. (2010) Roman Frontiers in Wales and the Marches. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales.

* this type of amphora was used primarily for transporting olive oil. It was made in the Roman province of Baetica, in what is now southern Spain. Kilns were distributed at numerous sites along the Guadalquivir valley.